FIDONET: When BBSes Went Global (And My Phone Bill Exploded)

How a network of dial-up BBSes connected the world using store-and-forward magic, and why getting a FIDONET address felt like joining some kind of digital secret society

Okay, picture this: You’re sitting in your bedroom in 1989, connected to your local BBS via your trusty 2400 baud modem, and suddenly you realize you can send a message to someone in Germany. Not through some fancy internet connection (because for most of us, that didn’t exist yet), but through this absolutely brilliant network called FIDONET that basically turned every participating BBS into a node in a global communications web.

This is the story of how a bunch of BBS sysops figured out how to connect the entire world using nothing but phone lines, modems, and some seriously clever store-and-forward magic.

Special thanks to Randy Bush’s comprehensive 1992 technical paper “FidoNet: Technology, Use, Tools, and History” for providing crucial historical details and statistics that help tell this story properly.

My First FIDONET Address (And Why It Felt Like Magic)

I still remember the first time I got a FIDONET address. The local sysop told me I was now 1:346/23.15 - and honestly, those numbers felt more important than my Social Security number.

Let me break down what that gobbledygook actually meant:

- 1 = Zone (North America - we were the cool kids)

- 346 = Net (my regional network)

- 23 = Node (the actual BBS I was on)

- .15 = Point (that was ME!)

Getting that address was like being handed the keys to the digital kingdom. Suddenly, I wasn’t just some kid dialing into local boards anymore. I was part of this global network that stretched across continents.

History of node 1:346/23

7 Jun 1991, nodelist.158: ,23,Wirehaired_Terrier_Opus_BBS,Spokane_Wa,Pat_Breeden,1-509-448-****,2400,CM,XW

4 Oct 1991, nodelist.277: Node removed from the nodelist

6 Dec 1991, nodelist.340: ,23,The_Diamond_Mine,Spokane_WA,Richard_Baysinger,1-509-325-****,2400,CM

28 Jun 1996, nodelist.180: ,23,The_Diamond_Mine,Spokane_WA,Richard_Baysinger,1-509-325-****,9600,CM

1 May 1998, nodelist.121: Node removed from the nodelistLooking at this history from the actual FidoNet nodelists, you can see the story of node 1:346/23 from 1991 to 1998. First it was Pat Breeden’s “Wirehaired Terrier Opus BBS” (what a name!), then after a brief gap, Richard Baysinger took over with “The Diamond Mine.” That jump from 2400 to 9600 baud in 1996 was probably a big deal for users back then. These nodes were real people running real systems, and each entry represents someone’s dedication to keeping the network alive.

The Humble Beginning: Two Friends Just Wanted to Share Messages

The whole thing started way simpler than you’d think. In 1984, Tom Jennings wasn’t trying to revolutionize global communications. He just wanted to move messages from his MS-DOS-based Fido BBS to his friend John Madil’s board. That’s it! No grand vision, no business plan, just two friends who wanted to share messages.

In Tom’s own words from his 1985 historical document: “When FidoNet was first tested, there were two nodes: myself here at Fido #1 in San Francisco, and John Madill at Fido #2 in Baltimore. John and I did all of the testing and development for the first pass at FidoNet. Its purpose: to see if it could be done, merely for the fun of it, like ham radio.”

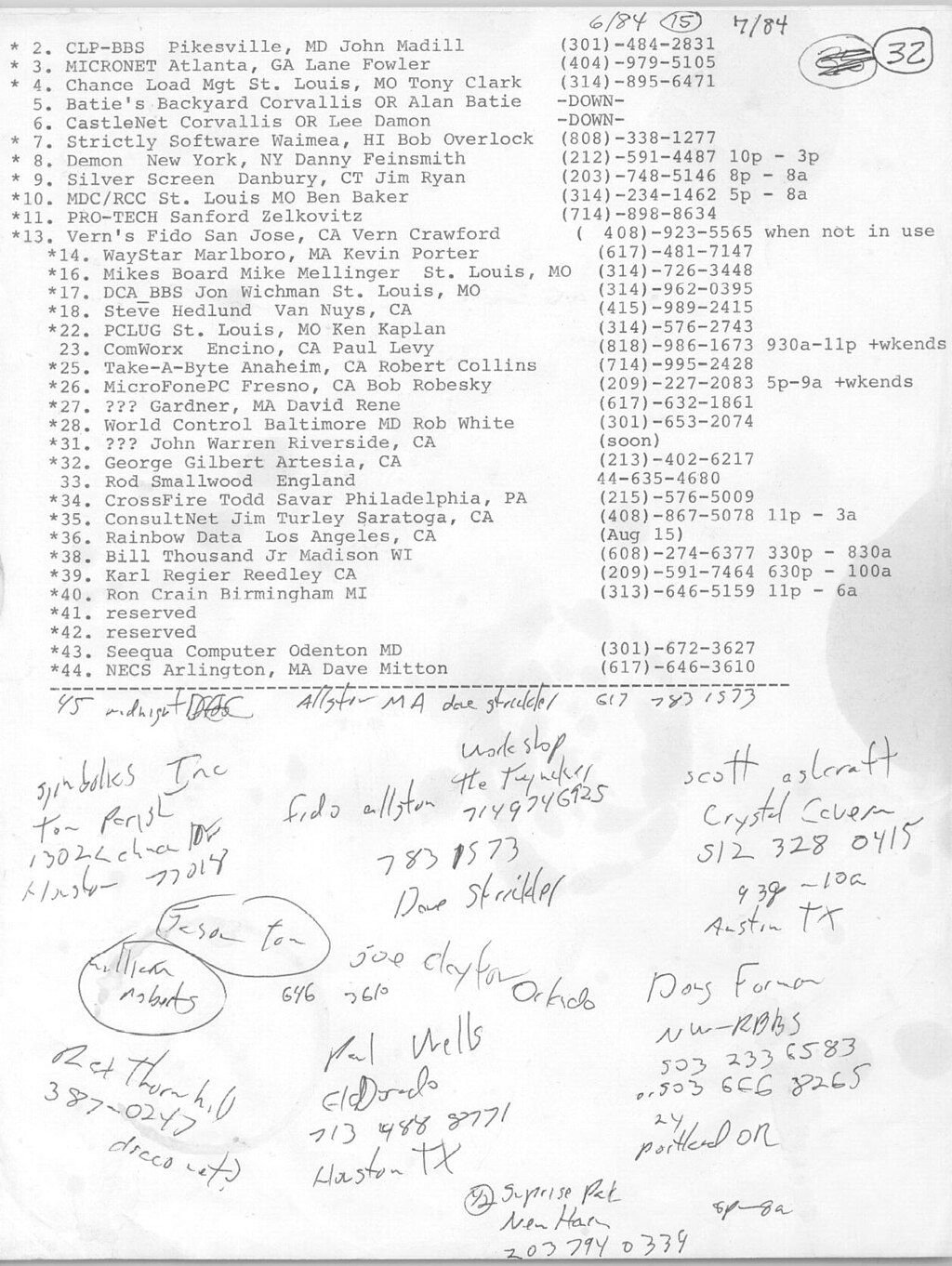

The very first Fido network listing from June 1984 - just a handful of nodes that would grow into a global network of 20,000+ systems

The very first Fido network listing from June 1984 - just a handful of nodes that would grow into a global network of 20,000+ systems

Since Jennings was the author of the Fido BBS software, he was able to quickly hack it to extract messages from a special local message area and queue them for sending to the remote BBS. And because US phone rates were way cheaper in the middle of the night, he wrote a separate program to handle this email transfer during one designated hour.

But here’s the part that gets me: Tom admits this first version “did not have routing, file attach, retry control, error handling, cost accounting, log files, or any of the niceties since added. A packet was made, a call placed, the packet transferred, that was it.”

__

/ \

/|oo \

(_| /_)

_`@/_ \ _

| | \ \\

| (*) | \ ))

______ |__U__| / \//

/ FIDO \ _//|| _\ /

(________) (_/(_|(____/

(c) John Madill

FidoNet logo by John MadillThis single late-night hack between friends became the foundation for a global network that would eventually connect 20,000 nodes worldwide.

The Beautiful Chaos of Store-and-Forward

Here’s where FIDONET got really wild. This wasn’t real-time communication like we’re used to today. This was store-and-forward, which basically meant your message took a journey that would make the Pony Express jealous.

You’d write a message to someone on a BBS in, say, Australia. That message would sit on your local board until mail hour (usually late at night when phone rates were cheaper). Then your BBS would dial up its “uplink” - usually some bigger, more established board - and dump all the outbound mail.

From there, your message would hopscotch across the network: local hub to regional hub to national hub to international gateway, probably bouncing through multiple time zones and phone systems before finally landing on some BBS in Melbourne days later.

The crazy part? It actually worked. This was 1989, remember. Most people still thought computers were just fancy calculators, and here we were running a global communications network using equipment that would barely qualify as a calculator today.

The Numbers That’ll Blow Your Mind

By 1992, FidoNet had grown to absolutely insane proportions. We’re talking about over 20,000 public nodes worldwide moving email and news over regular phone lines. To put that in perspective, here’s how explosive the growth was:

.svg.png) The explosive growth of FidoNet nodes from 1984 to 1995 - from Tom and John’s two-node experiment to a global network of over 20,000 systems

The explosive growth of FidoNet nodes from 1984 to 1995 - from Tom and John’s two-node experiment to a global network of over 20,000 systems

- 1984: 100 nodes (Tom and his friends)

- 1985: 600 nodes

- 1986: 1,400 nodes

- 1987: 2,500 nodes

- 1988: 4,000 nodes

- 1989: 6,500 nodes

- 1990: 9,000 nodes

- 1991: 11,000 nodes

- 1992: 16,000 nodes

- 1993: 20,000 nodes

That’s a 200x growth in under a decade, all volunteer-run!

But here’s the part that really gets me: 2 million people were reading or writing FidoNet echomail by 1992, with about 200,000 using private email. And they were moving over 8 megabytes of compressed echomail daily. In 1992! When most people thought 640KB was plenty of memory for anyone.

This wasn’t just some hobbyist network either. AT&T, Georgia Pacific, and the Canadian Post Office were running private FidoNet networks alongside the public one. Major corporations saw the value in this “amateur” technology and were quietly using it for their own internal communications.

Here’s the complete timeline showing FidoNet’s incredible journey from Tom and John’s two-node experiment to a global network of over 35,000 systems:

timeline

title FidoNet Evolution: From Two Friends to Global Network

1983 : 💾 Fido Software v1.0 Released

: Tom Jennings creates the foundation

1984 : 📞 First Interstate Message

: Tom (SF) to John Madill (Baltimore)

: 2 nodes → 29 nodes → 100 nodes → 132 nodes

: 📝 First paper nodelist typed

: 🔀 Routing begins

: 📰 FidoNews launches

: 🌍 First intercontinental message (Indonesia)

1985 : 🏗️ The Great Architecture Year

: 🍕 Echomail conceived at Dallas pizza party

: ⏰ 10-hour meeting in Kaplan's living room

: 🔄 June 12th "Great Switch" (300+ nodes coordinate)

: 📋 Hierarchical addressing system born

1986 : 📜 Policy & Standards

: 📖 FidoNet Policy Guide issued

: 💬 Echomail introduced by Jeff Rush

: 🔧 FTSC Technical Standards Committee formed

: 📊 938 nodes

1987 : 🌐 Global Zones Established

: 🗺️ Zone system implemented

: 🇺🇸 North America (z1), 🇪🇺 Europe (z2), 🇦🇺 Oceania (z3)

: 📋 First Echomail Conference List

: 📈 1,935 nodes

1988 : 🔗 Internet Integration Begins

: 🌍 Africa and South Africa added

: 💻 FidoNet connected to Internet

: 📊 2,307 nodes

1989 : 📐 Policy & Expansion

: 🌎 Zone 4 (Latin America) joins

: 🌍 Zone 5 (Africa) joins

: 📜 Policy 4.07 adopted

: 📈 4,722 nodes

1990 : ⚙️ Infrastructure Maturity

: 📮 Routed netmail implemented

: 🎪 First FidoCon conferences begin

: 📊 5,692 nodes

1991 : 🌏 Complete Global Coverage

: 🇯🇵 Zone 6 (Asia) completes 6-zone system

: ✅ All current zones established

: 📈 9,138 nodes

1992 : 🏆 Recognition & Peak Growth

: 🥇 Tom Jennings receives EFF Pioneer Award

: 📊 12,771 nodes

1993 : ⭐ Mainstream Recognition

: 🏆 Ward Christensen receives EFF Pioneer Award

: 💾 Nodelist passes 2MB mark

: 📈 18,588 nodes

1994 : 📰 Professional Standards

: 🆔 FidoNews gets ISSN number

: 📊 25,159 nodes

1995 : 🎯 THE PEAK

: 🚀 June: 35,787 nodes - Maximum size achieved!

: 💾 Nodelist over 3MB

: 🎪 Last ONE BBSCon conference

1996-2001 : 🌐 Internet Era Transition

: 1996: 34,038 nodes (Internet adoption accelerates)

: 1997: 29,027 nodes (FidoNews.org goes online)

: 1998: 22,929 nodes

: 1999: 18,088 nodes

: 2000: 15,408 nodes

: 2001: 13,293 nodes (Legacy continues)Complete timeline of FidoNet’s evolution from 1983-2001, showing the incredible growth from 2 nodes to over 35,000 systems worldwide

The Midnight Mail Runs (And Why Sysops Never Slept)

Being a FIDONET sysop was like being a digital mail carrier who worked the graveyard shift. The whole network ran on this carefully choreographed dance that happened every night during off-peak phone hours.

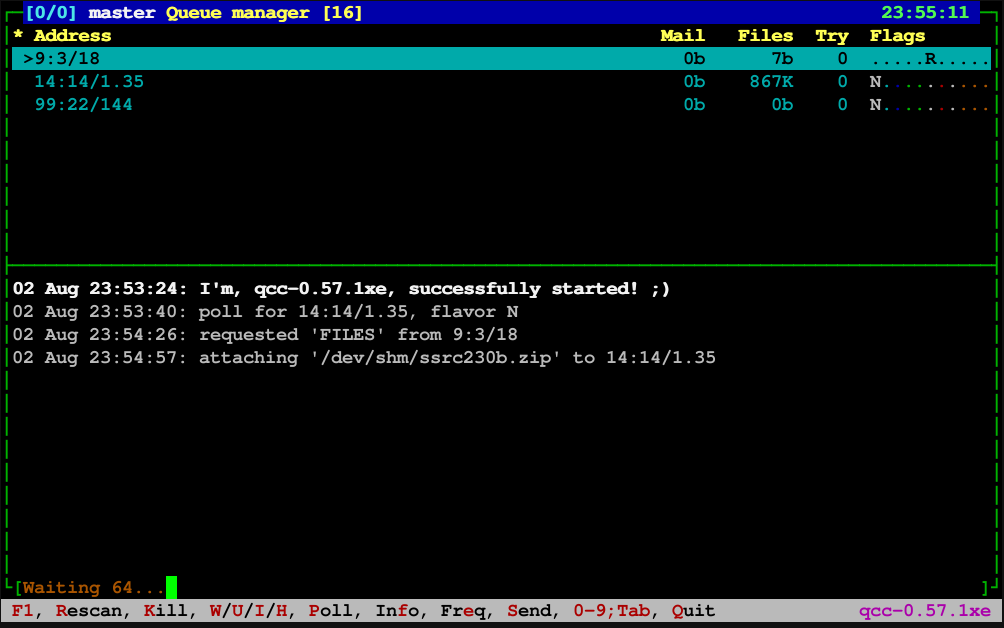

A mail queue management interface showing the complex logistics of routing messages across the FidoNet - sysops had to monitor these systems to ensure mail flowed properly

A mail queue management interface showing the complex logistics of routing messages across the FidoNet - sysops had to monitor these systems to ensure mail flowed properly

Picture this: Around midnight, BBSes all across the country would start dialing each other up like some kind of electronic square dance. Your local board would call its uplink, receive any incoming mail, send out the day’s messages, maybe grab some file updates, and then hang up.

If you were unlucky enough to try calling your BBS during “mail hour,” you’d get nothing but busy signals. The sysop was probably sitting there watching scrolling text on a terminal, making sure the mail run completed successfully, because if it failed? No FIDONET mail until tomorrow night.

I knew one sysop who had his system set up to call him if the mail run failed. Guy’s phone would ring at 3 AM, and he’d have to get up and figure out why his board couldn’t connect to its uplink. Talk about dedication.

The Politics of Uplinks (Or: Why Geography Mattered)

Getting connected to FIDONET wasn’t as simple as just installing software. You had to find an uplink - basically a bigger BBS that would agree to carry your mail. This created this whole hierarchical system that was part technical necessity, part digital politics.

If you were running a small BBS in some tiny town, you’d probably connect to a bigger board in the nearest city. That board would connect to a regional hub, which connected to a national backbone, and so on up the chain.

The wild part was that geography still mattered in this digital network. A message from Portland to Seattle might actually route through Chicago, depending on how the networks were set up. Long-distance phone charges meant that the most direct route wasn’t always the cheapest route.

Echo Areas: The Original Forums

FIDONET’s killer feature was Echo Areas - basically distributed message boards that existed across multiple BBSes simultaneously. You could post a message to “HOBBIES.COMPUTERS” on your local board, and that message would propagate out to every BBS that carried that echo.

Some of the popular echoes were legendary:

- FIDO_SYSOP - Where sysops talked shop and complained about users

- HOBBIES.COMPUTERS - Endless debates about which computer was best

- ALT.MUSIC - Before there was MP3 trading, there were album reviews

- COOKING - Surprisingly active, even back then

- POLITICS - Exactly as civilized as you’d expect

The beauty was that you could participate in these global discussions without ever leaving your local BBS. Your sysop would subscribe to whatever echoes they thought their users would want, and boom - instant global community.

The Great FidoNet Coup Attempt of 1989 (No, Really)

Here’s a story that sounds like it came straight out of a cyberpunk novel, but it’s absolutely true. In 1986, this well-intentioned but naive group formed the International FidoNet Association (IFNA), supposedly to help promote the technology and coordinate newsletters.

But by 1989, things had gotten political. Really political.

Some less-than-constructive elements within IFNA decided they wanted to take complete control of the entire FidoNet network. So they attempted to load the IFNA board of directors and pass a motion that would put IFNA in charge of everything.

This was basically a digital coup attempt.

But here’s where it gets beautiful: FidoNet fought back with the most 1980s BBS thing possible. They forced the takeover attempt into FidoNet’s only global referendum ever - a network-wide vote that required a majority of the entire network to agree to IFNA rule.

Picture thousands of sysops and users across six continents debating this in echo areas, and then actually voting via the same store-and-forward network they were fighting over.

The result? The coup failed spectacularly. The network voted down the takeover, IFNA was subsequently dissolved, and FidoNet remained the “cooperative anarchy” that Tom Jennings had always intended.

This whole episode proved something incredible about FidoNet’s design: because every node had the phone numbers of every other node and could communicate directly, no central authority could actually control the network. It was truly owned by its users.

When Things Went Wrong (And They Often Did)

FIDONET was amazing when it worked, but when it broke? Oh boy.

But before we get to the technical problems, let me tell you about the human problems. Tom Jennings tells this incredible story from the early days when wrong phone numbers were a constant issue:

“To impress on you the seriousness of wrong numbers in the node list, imagine you are a poor old lady, who every single night is getting phone calls EVERY TWO MINUTES AT 4:00AM, no one says anything, then hangs up. This actually happened; I would sit up and watch when there was mail that didn’t go out for a week or two, and I’d pick up the phone after dialing, and was left in the embarrasing position of having to explain bulletin boards to an extremely tired, extremely annoyed person.”

Can you imagine? Some poor lady getting hammered with modem calls in the middle of the night because her number got into the FIDONET node list by mistake. Tom would have to call her up and try to explain what a bulletin board system was to someone who just wanted to sleep!

Duplicate messages were a constant problem. You’d post something once, and through some routing hiccup, it would appear three times in the echo. Multiply that by hundreds of users, and echo areas would turn into digital Groundhog Day.

Mail loops were even worse. A misconfigured node would create an infinite loop where messages would just bounce back and forth forever, eating up bandwidth and driving sysops crazy.

And don’t get me started on net splits. When a major hub went down, entire regions would get cut off from the network. Suddenly, the West Coast couldn’t talk to the East Coast, and everyone assumed the other side had disappeared.

But you know what? The fact that this volunteer-run, amateur network worked at all was miraculous. People were literally running global communications infrastructure out of their spare bedrooms using consumer-grade equipment.

The 10-Hour Meeting That Saved FidoNet

Here’s one of my favorite stories from Tom’s historical documents. By 1985, FidoNet was growing so fast that it was literally about to collapse under its own weight. The node list was becoming unmanageable, and they desperately needed a solution.

Tom and Ezra Shapiro were invited to speak at the McDonnell Douglas Recreational Computer Club in St. Louis, and they planned ahead for a national FidoNet sysops meeting that same weekend. Ken and Sally Kaplan were kind enough to host everyone in their living room.

In Tom’s words: “The meeting lasted ten continuous hours; it was the most productive meeting I (and most others) had attended. When we were done, we had basically the whole thing layed out in every detail.”

Picture this: a bunch of computer geeks crammed into someone’s living room for 10 straight hours, designing what would become the hierarchical addressing system that made global networking possible. No corporate boardrooms, no venture capital, no project managers. Just passionate volunteers figuring out how to connect the world.

Tom continues: “Two or three months of brainstorming just flowed smoothly into place in one afternoon… What we had done was exactly what we have now.”

That meeting in the Kaplans’ living room created the net/node addressing system (like 1:346/23.15) that allowed FidoNet to scale from hundreds to thousands of nodes. When you consider that this volunteer-designed system influenced how the entire internet would eventually be structured, it’s pretty amazing that it all started with folks sitting on someone’s couch.

The Day They Switched the Entire Network (June 12, 1985)

Once they had the new system designed, they faced an incredible challenge: how do you upgrade 300 volunteer-run systems spread across multiple continents to a completely new addressing scheme, all at the same time?

The solution was both elegant and terrifying: a coordinated global switch on June 12th, 1985.

Tom describes the anxiety: “Finally, on June 12th, we all swapped over to the new system; that afternoon, sysops were to set their net number (it had been ‘1’ for backwards compatibility), copy in the new node list issued just for this occasion, and go. I assumed the result was going to be perpetual chaos, bringing about the collapse of FidoNet.”

Think about what they were attempting: hundreds of sysops, most of whom had never even talked to each other, all had to coordinate changing their systems at exactly the same time. No central authority could force this to happen. It had to work through pure community cooperation.

And it actually worked.

Tom was amazed: “Almost the exact opposite was true; things went very smoothly (yes, there were problems, but when you consider that FidoNet consists of microcomputers owned by almost 300 people who had never even talked to each other…)”

Within a month, virtually every system had successfully transitioned to the new net/node architecture. This kind of coordinated upgrade across a distributed volunteer network was unprecedented - and probably hasn’t been matched since.

The Characters Who Made It Work

FIDONET attracted some absolutely fascinating people. You had:

The Network Coordinators - The digital equivalent of air traffic controllers, keeping the routing tables updated and settling disputes between nodes.

The Echo Moderators - Volunteers who tried to keep discussions on-topic and civil. Good luck with that on ALT.POLITICS.

The Technical Wizards - People who understood the arcane details of routing protocols and could debug why mail wasn’t flowing properly.

The Troublemakers - Every network had them. Users who would deliberately stir up drama in the echoes or abuse the system in creative ways.

The amazing thing was that it was all volunteer-run. Nobody was getting paid for this. People maintained nodes, coordinated networks, and kept the whole thing running because they believed in the vision of global communication.

The Economics of Connection

Running a FIDONET node wasn’t cheap. You needed:

- Dedicated phone lines (because mail hour tied up your board for hours)

- Long-distance charges to your uplink

- Extra storage for all the mail and echo traffic

- Backup power (because losing power during a mail run was a disaster)

Some sysops were spending hundreds of dollars a month just on phone bills. The bigger hubs were probably spending more on telecommunications than most small businesses.

But here’s the thing: they did it anyway. Because being part of this global network was worth the cost. You weren’t just running a local BBS anymore; you were part of something bigger.

The Secret Internet Hack That Saved FidoNet Thousands

Here’s something most people don’t know: by November 1991, FidoNet was already using the Internet to transport mail and news between Europe and North America. This wasn’t some official partnership - it was a brilliant hack that saved the network thousands of dollars a month.

Instead of expensive international phone calls, the European and North American zonegates were moving data directly via IP connections, courtesy of RIPE and EUnet. The data wasn’t even being converted between formats - they were literally tunneling FidoNet protocols through the Internet.

By late 1992, this Internet tunneling had expanded to Taiwan, Southern Africa, Chile, and other regions. FidoNet was basically using the Internet as a free long-distance carrier while most people didn’t even know what the Internet was.

Think about that: while the general public was still trying to figure out what email was, FidoNet sysops were already running hybrid networks that seamlessly bridged dial-up and Internet protocols. These folks were decades ahead of their time.

When I Accidentally Became Internet Famous

I’ll never forget the time I posted what I thought was a harmless message to a computer echo, and somehow it ended up sparking this massive debate that spread across multiple echo areas for weeks.

The message eventually made it all the way to boards in Europe and Australia. I was getting replies from people I’d never heard of, in countries I’d only seen on maps. For a kid who’d been kicked off local BBSes for being too young, suddenly having my thoughts read by people around the world was absolutely mind-blowing.

That’s when I really understood what FIDONET was: it wasn’t just a technical achievement, it was a community that happened to span the globe.

The Original Social Media Rule (From 1985!)

You want to know what’s amazing? FidoNet’s basic social guideline, established way back in 1985, was elegantly simple. From Tom’s own historical document, the network’s purpose was described as “a hobby, a non-commercial network of computer hobbiests (‘hackers’, in the older, original meaning) who want to play with, and find uses for, packet switch networking.”

The operating principle was basically: “Do not be excessively annoying and do not become excessively annoyed.”

That’s it. No 50-page terms of service, no complex community standards, no algorithmic content moderation. Just a perfectly reasonable request for people to not be jerks to each other.

Tom also emphasized that it was “similar to ham radio, in that other than a few ‘stiff’ rules, each sysop runs their system in any way they please, for any reason they want.”

Honestly, if modern social media platforms adopted this single rule, the internet would be a much more pleasant place. The fact that a global network of thousands of volunteers managed to function under this simple guideline says something profound about what’s possible when people approach technology with genuine goodwill.

The Beginning of the End

FIDONET’s golden age couldn’t last forever. As the internet became more accessible and affordable, the elaborate infrastructure of hubs and uplinks started to seem quaint.

Why wait days for a message to propagate through the network when you could send email instantly? Why deal with mail hour and busy signals when you could connect to the web anytime?

But for those of us who lived through it, FIDONET represented something special: decentralized communication built by volunteers who believed in connecting people across the world.

What FIDONET Taught Us

Looking back, FIDONET was a preview of everything the internet would become:

- Global communication without central authority

- Distributed networks that could route around damage

- Online communities organized around shared interests

- Store-and-forward messaging (hello, email!)

- User-generated content before anyone called it that

The technical principles that made FIDONET work - packet routing, store-and-forward, hierarchical addressing - are still fundamental to how the internet operates today.

But more than that, FIDONET proved that ordinary people could build extraordinary things. No corporations, no government funding, no venture capital. Just a bunch of computer geeks with modems and phone lines who wanted to talk to each other.

The Legacy Lives On

While the original FIDONET network is mostly a memory now, its spirit lives on everywhere you look. Discord servers, Reddit communities, mesh networks, even blockchain systems - they all trace their DNA back to those early days when sysops were figuring out how to connect BBSes across the world.

And honestly? In our age of centralized social media platforms and corporate-controlled communication, there’s something refreshing about remembering a time when the network was owned by its users.

FIDONET wasn’t just a technical achievement. It was proof that given the right tools and the right motivation, people will build amazing things together. Even if it means staying up until 3 AM to debug why the mail run to Australia keeps failing.

The store-and-forward revolution: when BBSes went global, one dial-up connection at a time.

Sources and Further Reading:

- Randy Bush, “FidoNet: Technology, Use, Tools, and History” (1992) - Available at fidonet.org

- Tom Jennings, “FidoNet History and Operation” (February 8, 1985) - Originally at worldpowersystems.com/FidoNet/fidohist1.txt

- Tom Jennings, “FidoNet History and Operation Part Two” (August 20, 1985) - Originally at worldpowersystems.com/FidoNet/fidohist2.txt

- Personal experience and nodelist archives from 1:346/23

Want more stories from the dial-up days? Check out our other posts about BBS door games and the wild world of Renegade BBS.