David Hockney’s Fax Art Revolution: When Artists Hijacked the Office Machine

How one artist figured out that screeching office equipment could create revolutionary art, and why his phone bills went through the roof

So here’s something that’ll blow your mind: in 1989, David Hockney participated in one of the world’s biggest art exhibitions by faxing his entire contribution from Hollywood to São Paulo. We’re talking 144 individual fax pages that had to be assembled like a giant puzzle on the other side of the planet.

Think about that for a second. While everyone else was shipping paintings in crates and dealing with customs nightmares, this guy was using the same technology your office used to send invoices to create museum-quality art. And honestly? It worked so well that people are still paying tens of thousands of dollars for these “fax drawings” at major auctions.

This is the story of how David Hockney turned the humble fax machine into something nobody saw coming: a revolutionary artistic medium.

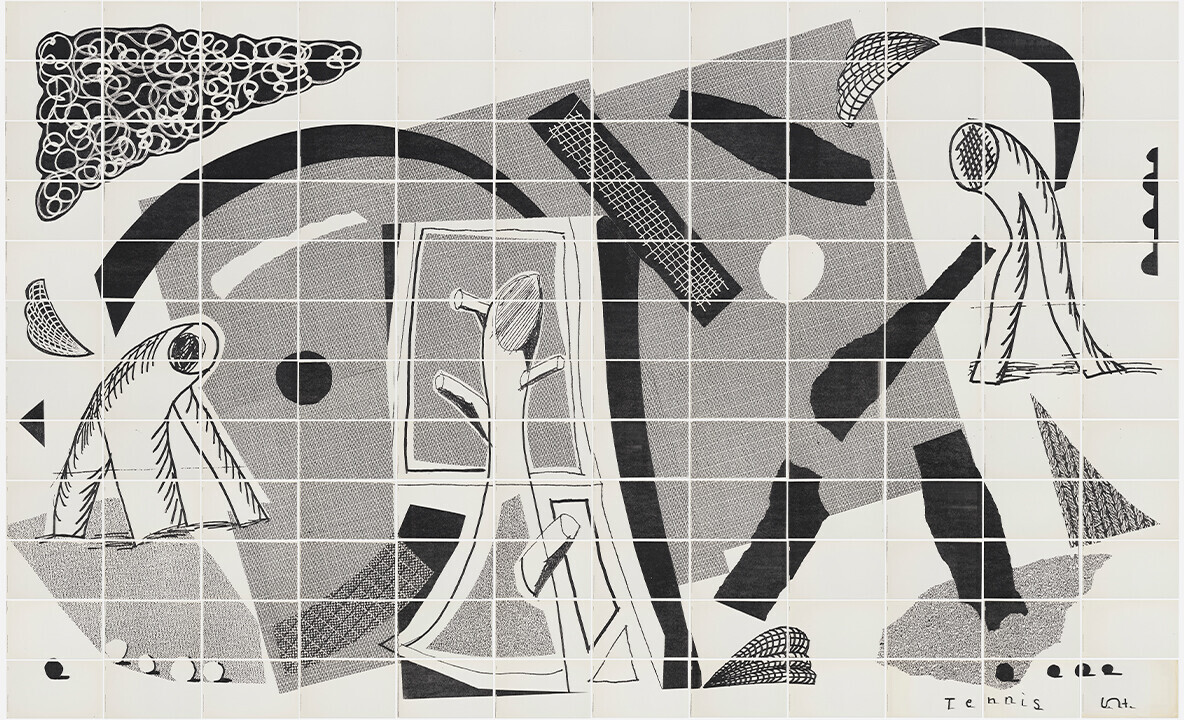

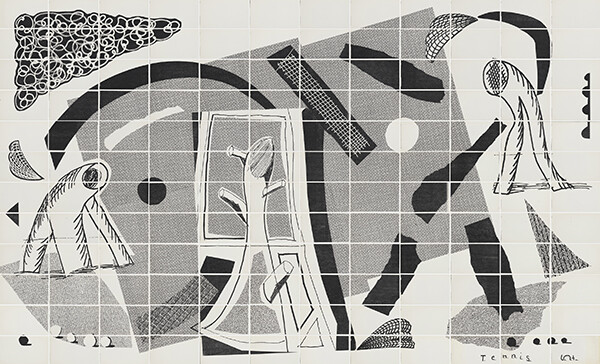

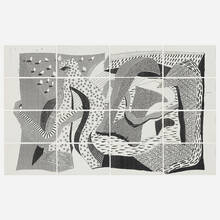

Detail of “Tennis” showing how the fax machine converted Hockney’s gray tones into distinctive dot patterns. Pretty wild how office equipment could create these effects, right?

”The Wonderful Machine, The Enemy of Totalitarianism”

That’s actually what Hockney called the fax machine. While the rest of us saw boring office equipment, this guy saw something revolutionary: instant global art distribution without gatekeepers.

You gotta understand the context here. In the 1980s, if you wanted to show your art internationally, you were looking at weeks of shipping, insurance paperwork, customs forms, the whole bureaucratic nightmare. But fax? You could literally draw something in California and have it appear in Brazil 30 minutes later.

Hockney started experimenting with fax in the mid-80s, just sending drawings to friends around the world for fun. Word got out, and people started calling him asking, “Hey David, can you fax me your latest piece?” His phone bills, as he put it, became “enormous.” (Gotta love an artist who treats international phone charges as a legitimate art expense.)

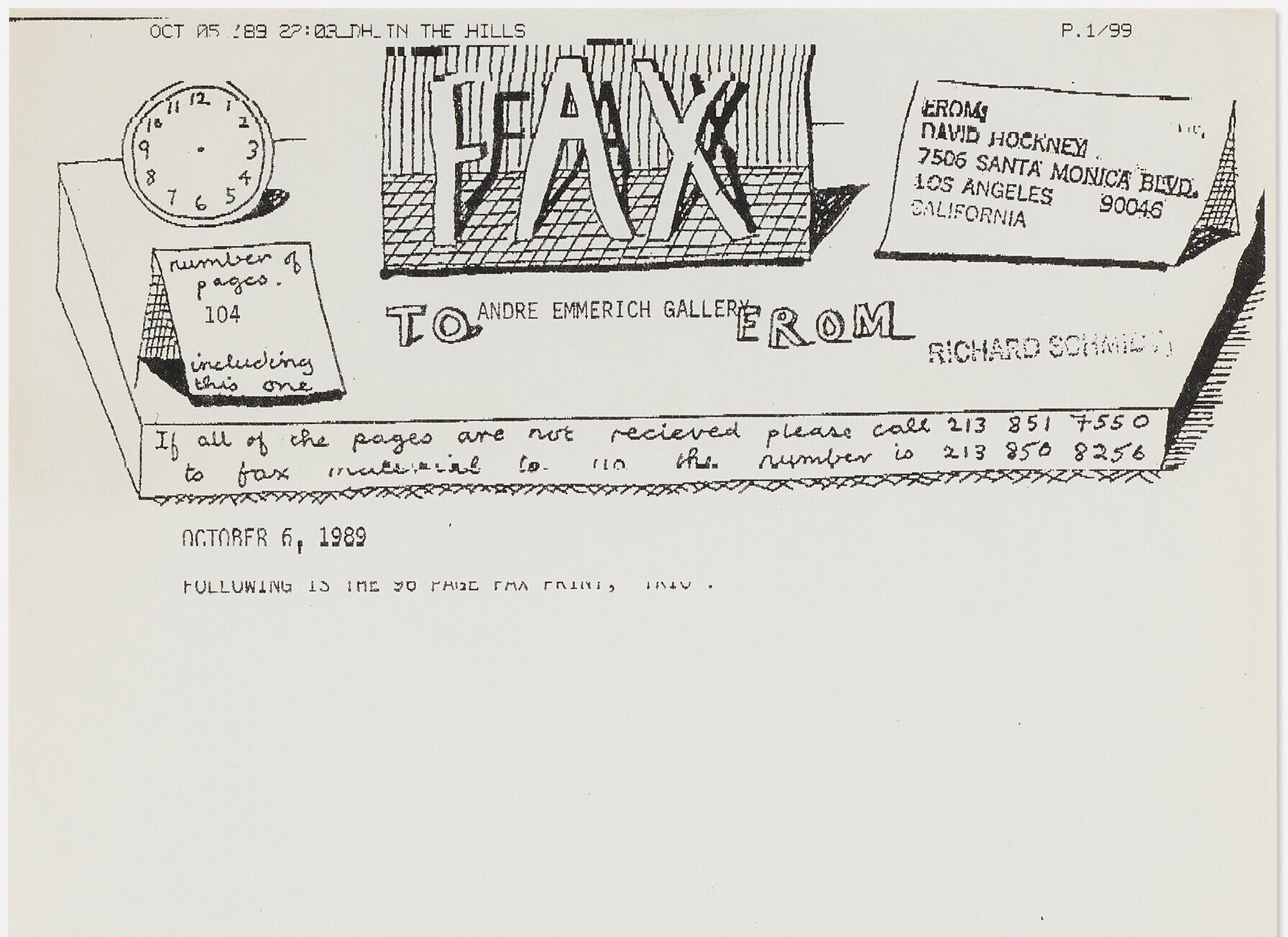

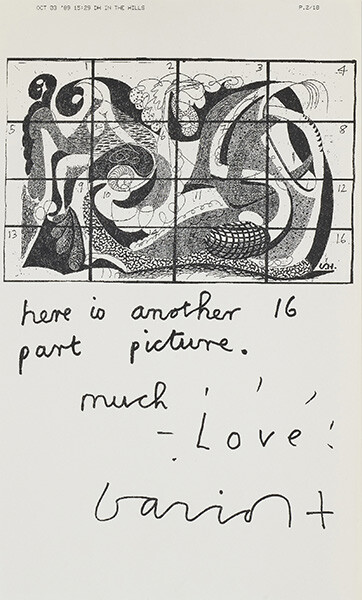

Hockney’s handwritten statement about the fax project - itself transmitted by fax. The irony is perfect.

The Hollywood Sea Picture Supply Co.

By 1988, Hockney was so into this fax thing that he basically started his own art transmission company. He called it The Hollywood Sea Picture Supply Co. and operated from two locations:

- “DH at the beach” (his Malibu place)

- “DH in the hills” (Hollywood Hills studio)

Every fax page got timestamped and location-coded, turning each transmission into performance art. He wasn’t just making pictures; he was documenting the process of sending art through phone lines. Pretty genius when you think about it.

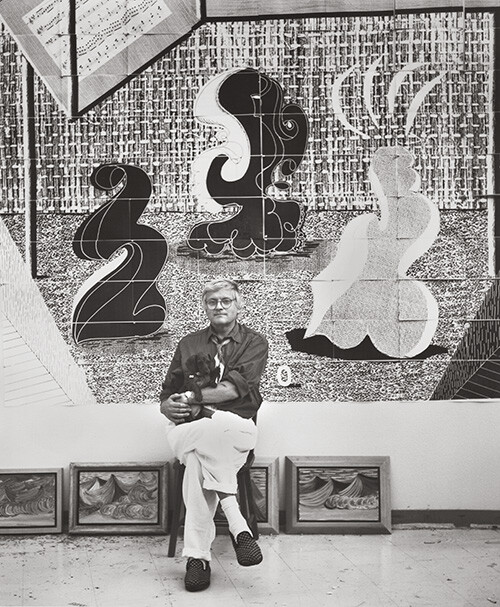

David Hockney with “Trio.” Photo courtesy Herb Ritts / AUGUST.

The São Paulo Challenge

When the 1989 São Paulo Biennial invited Hockney to participate, he had this crazy idea: what if he just faxed his entire exhibition to Brazil?

The curators probably thought he was joking. But Hockney was dead serious. He got a map of the exhibition space, built a scale model in his studio, and started designing fax artworks specifically for those walls. He calculated exactly how many fax pages each wall could handle and planned massive multi-sheet compositions accordingly.

We’re talking about 96-sheet and 144-sheet artworks that had to be assembled in Brazil like some kind of international art jigsaw puzzle. The logistics alone were insane.

The Technical Magic (And Why It Actually Worked)

Here’s where it gets really interesting. Hockney didn’t just adapt his art to work with fax machines - he figured out how to exploit the technology’s limitations as artistic features.

Fax machines in 1989 could only handle black and white, but they converted grayscale using these dithering algorithms that created amazing dot patterns. Instead of fighting this, Hockney started using opaque grays specifically to trigger these effects.

The result? The fax machine would automatically convert his drawings into something that looked like sophisticated halftone printing or pointillist techniques. But it was all happening automatically, in real-time, as the image transmitted.

For the technical folks: Group 3 fax standard, about 200 DPI resolution (which was actually pretty decent for 1989), thermal printing creating those distinctive dot patterns we see in the details.

The Major Works: Art Transmitted Via Phone Line

Let me walk you through some of the standouts from this collection:

Tennis - The 144-Sheet Monster

“Tennis” in its complete 144-sheet form. Each page had to be positioned perfectly to create this composition.

This thing is absolutely bonkers. 144 individual fax pages that created one massive tennis court scene. Hockney had to send detailed assembly instructions with grid references for each sheet.

When they later transmitted it to England for a gallery show, they played “Ride of the Valkyries” while assistants assembled all 144 pieces. (Because apparently that’s what you do when you’re making art history.)

People are paying $40,000-60,000 for this at auction. Not bad for something that came through a phone line.

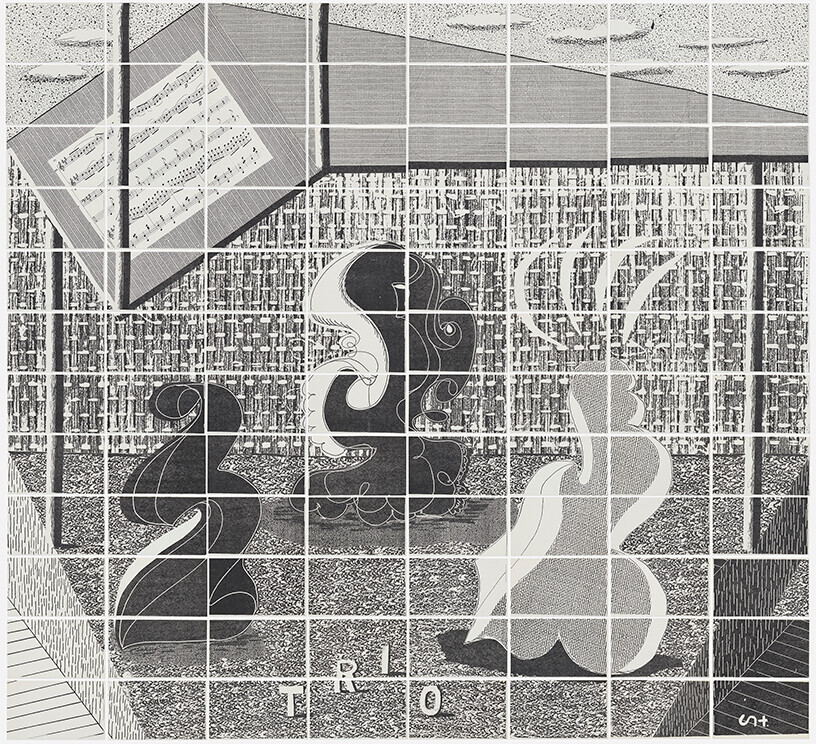

Trio - The 96-Sheet Experiment

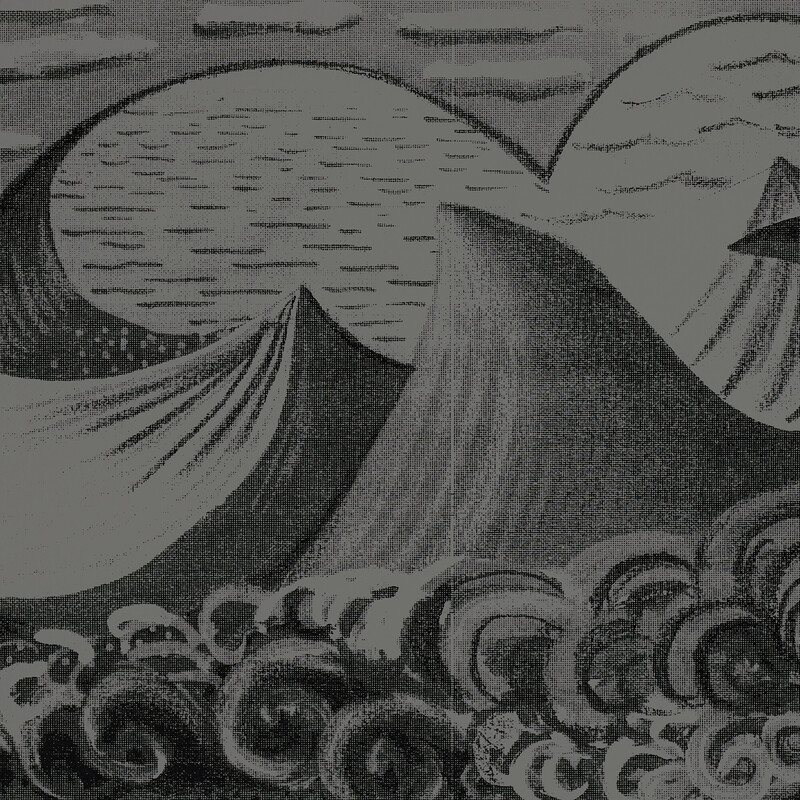

“Trio” shows how Hockney adapted his multi-perspective approach to fax. You can actually see the grid lines where sheets connect.

Another massive composition, this time 96 sheets showing three figures. What’s cool is you can see the demarcation lines between individual fax pages, and Hockney embraced these as part of the composition instead of trying to hide them.

Goes for $30,000-50,000 at auction.

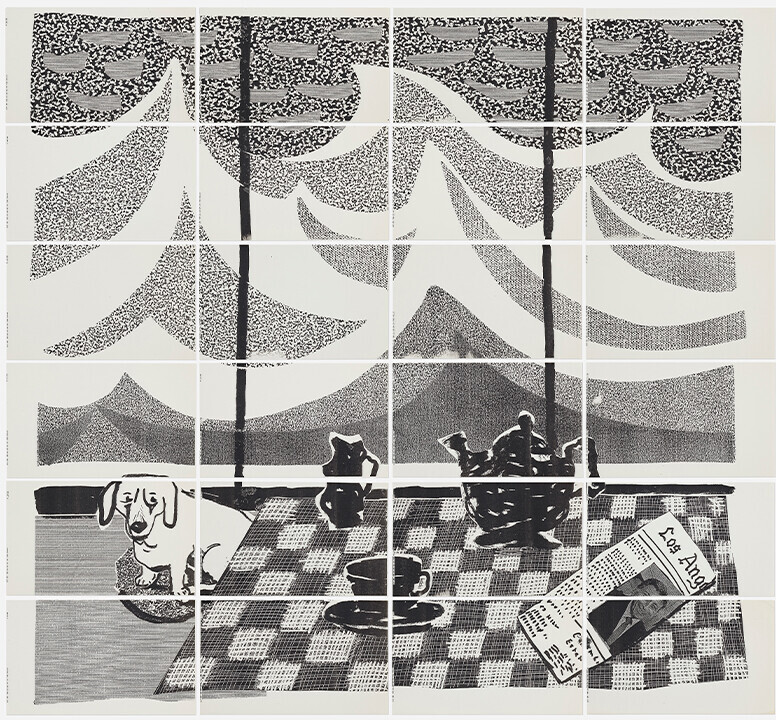

Breakfast with Stanley in Malibu

A 24-sheet domestic scene showing how the fax machine’s dot patterns could enhance the artwork.

This 24-page piece shows how the fax machine’s automatic dot conversion could actually improve the artwork, creating textures that mimicked pointillist techniques while keeping clear line definition.

Sold for $20,160.

The Single-Sheet Gems

Not everything was a massive multi-page epic. Some of Hockney’s best fax works were single sheets that really showed off what the medium could do:

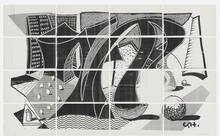

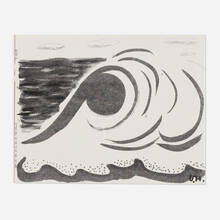

Hotel by the Sea - The fax machine’s dithering created atmospheric effects in the sky that Hockney couldn’t have predicted. Technology as creative partner.

Abstract Building - Shows how fax preserved sharp lines while converting tonal areas into dot patterns. Architecture meets telecommunications.

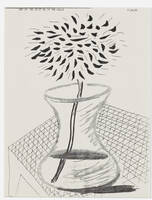

Still Life with Chair ($10,080) - The thermal printing created varying dot densities that enhanced depth and shadow. Who knew office equipment had artistic potential?

Sea and Cliffs ($10,080) - The fax’s binary system created gradations through dot density variations, producing unexpected effects in the water.

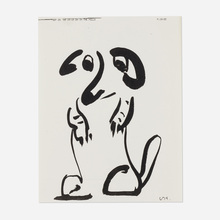

Stanley Sitting Up ($5,040) - Portrait showing how thermal printing preserved both drawing style and likeness through consistent dot patterns.

Views of the Sea ($5,040) - Multiple perspective piece where the fax transmission’s slight compression actually enhanced Hockney’s collage aesthetic.

Four Clouds Over Sea ($3,780) - Sky study where the machine’s halftone conversion created atmospheric effects like traditional printmaking.

Flower in Glass Vase ($3,528) - Still life showing the fax’s ability to render glass through dot pattern variations alone.

The Brazilian Phone Line Disaster

Here’s where things get hilarious. When it came time to actually transmit the São Paulo exhibition, the Brazilian phone lines couldn’t handle it. They were trying to send hundreds of fax pages internationally, and the infrastructure just wasn’t up for it.

The solution? They faxed everything from room to room in a Los Angeles hotel, then had an assistant carry the faxes to São Paulo in suitcases. So much for the futuristic vision of instant global art transmission!

But you know what? It worked. The exhibition was assembled in Brazil, and people were completely blown away.

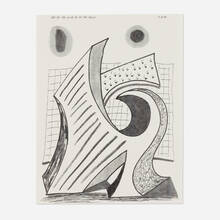

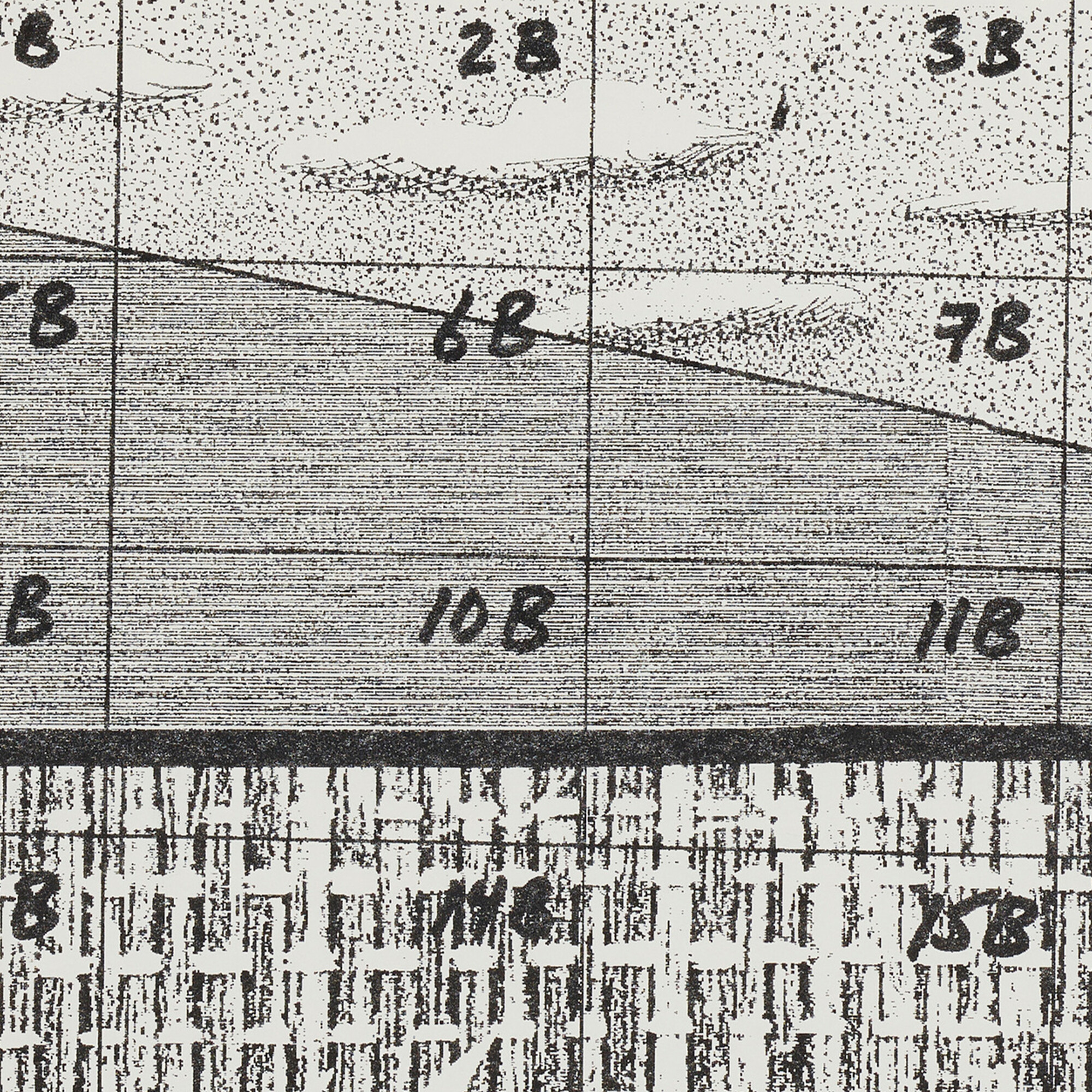

Hockney’s detailed assembly instructions for “Water and Edge” (1989). Note the grid references and positioning notes.

Why This Actually Mattered

Hockney’s fax art wasn’t just a cool gimmick. This was 1989 - the internet was barely a thing for regular people. Email was primitive. The idea of instant global communication was still science fiction for most of us.

But here was this artist showing that you could use existing telecommunications infrastructure to create and distribute art instantly around the world. He was basically previewing the digital age using analog phone lines.

The democratic aspect was huge too. Hockney loved that he could instantly send artwork to friends who might never afford a “real” Hockney. He was using mass communication tech to make art more accessible.

Plus, he was embracing the aesthetic limitations of the technology instead of fighting them. The grid lines, the dot patterns, the slight degradation - all of this became part of the artistic language.

The Technical Deep Dive

Close-up showing the fax machine’s dot matrix structure. Each dot represents a binary decision by the thermal printing system.

For the tech folks: Hockney would create drawings using opaque gray tones (washes didn’t transmit well). The fax scanner converted these into a bitmap at about 200 DPI. Then the dithering algorithm converted grayscale areas into patterns of black and white dots.

The genius was that Hockney figured out how to predict and control these automated processes to create specific visual effects. He wasn’t fighting the technology; he was collaborating with it.

Detail showing intersection of multiple fax sheets. The misalignments became part of Hockney’s compositional strategy.

What This Teaches Us

Here’s what I find most interesting about this whole thing: Hockney saw artistic potential in technology that everyone else considered purely functional. While the rest of us were using fax machines for boring office stuff, he saw them as creative tools.

That mindset - looking for unexpected creative potential in everyday technology - feels pretty relevant today. How many tools are we using for their “intended” purpose when they could be doing something completely different?

Plus, there’s something beautiful about art that took hours to transmit, one screeching line at a time. In our age of instant everything, there’s real charm in that patience and process.

The Legacy

These fax artworks were created on the cusp of the internet age. Within a few years, fax machines would start becoming obsolete. But somehow, these works capture a specific technological moment that’s already passed.

They’re like time capsules of a brief period when telecommunications was advanced enough to transmit complex images but still primitive enough to impose interesting limitations. And the art? The art endures.

People are still paying serious money for these pieces at major auctions. Not bad for something that came through a phone line.

Want more stories about artists who saw potential where others saw problems? Check out our other posts on technology that refused to die and vintage computing.

The complete Yunique Studio Collection represents Hockney’s full contribution to the 1989 São Paulo Biennial - and one of the most innovative uses of telecommunications in art history.